| |

A Resource by Mark D. Roberts |

|

Is the TNIV Good News? Volume 2 of 3

by Rev. Dr. Mark D. Roberts

Copyright © 2005 by Mark D. Roberts

Note: You may download this resource at no cost, for personal use or for use in a Christian ministry, as long as you are not publishing it for sale. All I ask is that you give credit where credit is due. For all other uses, please contact me at mark@markdroberts.com . Thank you.

What’s Wrong With the TNIV? “Him” to “Them” (Section B)

Part 11 of the series “Is the TNIV Good News?”

Posted at 11:55 p.m. on Sunday, February 27, 2005

Since my series was interrupted by weekend blogging, I’ll give a brief review of last Friday’s post before adding to it today.

In my last post in this series on the TNIV controversy I began to examine the first criticism found in the Statement of Concern signed by over 100 evangelical leaders who oppose the TNIV. This criticism is: “The TNIV translation often changes masculine, third person, singular pronouns (he, his and him) to plural gender-neutral pronouns.” The specific example given in the Statement of Concern is Revelation 3:20. Let me reproduce this verse in the NIV and the TNIV, with the differences in italics:

Here I am! I stand at the door and knock. If anyone hears my voice and opens the door, I will come in and eat with him, and he with me. (NIV)

Here I am! I stand at the door and knock. If anyone hears my voice and opens the door, I will come in and eat with them, and they with me. (TNIV)

This, according to the TNIV’s critics, is unacceptable. Here’s exactly what they say:

For example, in Revelation 3:20, the words of Jesus have been changed from "I will come in and eat with him, and he with me" to "I will come in and eat with them, and they with me." Jesus could have used plural pronouns when He spoke these words, but He chose not to. (The original Greek pronouns are singular. In hundreds of such changes, the TNIV obscures any possible significance the inspired singular may have, such as individual responsibility or an individual relationship with Christ.

In my last post I began going line by line through this criticism. I expressed my concern about the language of the first sentence, which could easily be misunderstood as accusing the TNIV translators as changing the actual words of Jesus found in the Greek manuscripts of Revelation. I wished that the TNIV critics would exercise more caution and clarity when talking about the TNIV’s so-called “changes.” Nevertheless, they truly point out where the TNIV differs from the NIV, changing “him” to “them and “he” to “they.”

| Moving on in the Statement of Concern we read: “Jesus could have used plural pronouns when He spoke these words, but He chose not to. (The original Greek pronouns are singular.)” It is surely correct that Jesus could have used plural pronouns if he had wanted. I’m glad the Statement adds the parenthetical comment about the “original Greek pronouns” being singular. Without this I’d have the same concern as before, since we cannot know for sure what pronouns Jesus might have used if he had been speaking American English of 2005. The Statement almost seems to imply that because Jesus chose Greek singular pronouns almost two millennia ago, we must also use singular pronouns today. But this begs the question of how best to translate auton and autos into contemporary English. |

|

|

What Language Did Jesus Speak?

Let me respond briefly to a number of questions and comments I’ve received about the language of Jesus in Rev 3:20. I’ve done a whole blog series on the language(s) spoken by the earthly Jesus. In Revelation the situation is somewhat different than in the gospels. Jesus speaks, not in his “this worldly” form, but as the glorious Son of Man who has revealed himself to John. We really don’t know the original language of his communication. What we do know is that the only record we have of it is in Greek. Thus it’s sensible to speak as if Jesus were speaking Greek to John, rather than Aramaic, which John translated into Greek. This is what the Statement of Concern does. Presumably the victorious Son of Man was fluent in whatever language he chose to speak. |

|

Let me put this more simply. It is perfectly possible to believe that the victorious Son of Man intentionally used masculine singular Greek pronouns in Revelation 3:20, and at the same time to believe that the best rendering of these pronouns into current English would be as “them” or “they.” This isn’t a question about Greek or divine revelation so much as about contemporary English usage. I’ll have more to say about this soon.

The Statement of Concern continues:

In hundreds of such changes, the TNIV obscures any possible significance the inspired singular may have, such as individual responsibility or an individual relationship with Christ.

Here’s the punch line of the criticism. As applied to Revelation 3:20 we must wonder: Does the use of “them” and “they” in the TNIV “obscure any possible significance the inspired singular may have, such as individual responsibility or an individual relationship with Christ”? Again, it almost seems as if the critics are assuming that an inspired singular form in an ancient biblical language should always be translated with a singular form in English or the inspiration is lost. But every translator knows that this is not true, even the translators who worked on the English Standard Version (ESV).

The ESV is the most recent “word-for-word” translation, one that was produced by the leading TNIV critics, in fact. So with the ESV you have the best example of what the signers of the Statement of Concern would prefer. I should add that this translation is in fact an excellent example of a “formal equivalence” translation, one that might very well replace the NASB among those who prefer a strict word-for-word approach. I have found it to be fresh and clear. But there are many times when the ESV translates formally plural words in the original languages with single nouns in English, and formally singular words with plural nouns. The box below provides several examples. If you don’t need the detail, you can skip the chart.

Note: for more information about the ESV Bible, check the official ESV website. |

|

Plural in the Original Languages to Singular in English

Hebrew to English: The first verse in the Bible reads in the ESV, “In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth” (Gen 1:1). But if you were to look at the Hebrew words, you would find not the singular el (god) but the plural elohim (gods). Yet the ESV is surely correct in this case to translate the Hebrew plural as an English singular.

Greek to English: The proclamation of Jesus in Matthew 3:2 reads in the ESV: “Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand.” The underlying Greek does not use the singular for “heaven” (ouranos in Greek) but the plural “heavens” (ouranoi). Once again the ESV hasn’t made an error by changing from plural to singular. The translators have understood correctly that what Jesus meant by using a plural noun in his own tongue is best rendered in a singular English noun today.

Singular in the Original Languages to Plural in English

Hebrew to English: Psalm 109:25 reads in the ESV: “I am an object of scorn to my accusers; when they see me, they wag their heads.” The original Hebrew uses an expression which literally reads “they wag their head: (singular ro’sh). Again, the ESV makes the right decision about the best English words and changes the number of the noun. (In a most curious exception to the ESV rule, when Psalm 44:14 uses that same Hebrew expression “wag their head” the ESV renders this as “[you have made us] a laughingstock among the peoples,” with “a shaking of the head” in a footnote. This is a fine example of dynamic equivalence, right in the middle of the ESV. Go figure!)

Greek to English: In Acts 18:6 the ESV has Paul saying, “Your blood be on your own heads!” The Greek reads literally, “Your blood [be] on your [pl] head [sing].” The change to plural “heads” in English makes the sense clearer. |

I recognize that these examples aren’t directly relevant to the question of gender language, but they help to point out that it’s a mistake to believe that all singular words in biblical languages should be translated as singular words in English. Sometimes it’s right to change the number in translation, as the ESV does in the instances I have cited above.

I know I’m probably boring some of my readers to death. But I believe that precision in detail is important here. After all, what is translation but paying attention to thousands upon thousands of details? When the TNIV critics refer to the significance of “the inspired singular” they almost seem to imply that the TNIV, by translating singular forms with plural forms, has lost or obscured the inspiration. But the critics’ own translation correctly shows that sometimes the inspired number in one language should be changed in translation. This does not mean, of course, that it’s right to do this in Revelation 3:20. If you check the ESV, it’s no surprise to find the singular “eat with him” and “he with me.” My point is that, in general, one cannot assume that some “inspired singular” in the original language must be preserved as singular in the target language of translation. Respect for biblical inspiration sometimes leads a translator to change from singular to plural or from plural to singular.

So what about the TNIV’s translation in Revelation 3:20, where “eat with auton (Gk sing)” becomes “eat with them” and “autos (Gk sing) with me” becomes “they with me”? Do these translations get it right? Are they defensible? Or do they obscure the possible significance of the singular? And do they subtract from individual responsibility or individual relationship with Christ?

This post is going on too long to finish up looking at Revelation 3:20. I’ll pick up the conversation tomorrow without much of an introduction so I can get right into the question of whether the TNIV obscures the singular meaning of this verse. Stay tuned . . . .

What’s Wrong With the TNIV? “Him” to “Them” (Section C)

Part 12 of the series “Is the TNIV Good News?”

Posted at 11:55 p.m. on Monday, February 28, 2005

Today’s post continues what I’ve been working on the last couple of days: a close analysis of a portion of the Statement of Concern over the TNIV Bible translation. This portion reads:

The TNIV translation often changes masculine, third person, singular pronouns (he, his and him) to plural gender-neutral pronouns.For example, in Revelation 3:20, the words of Jesus have been changed from "I will come in and eat with him, and he with me" to "I will come in and eat with them, and they with me." Jesus could have used plural pronouns when He spoke these words, but He chose not to. (The original Greek pronouns are singular.) In hundreds of such changes, the TNIV obscures any possible significance the inspired singular may have, such as individual responsibility or an individual relationship with Christ.

So far I’ve expressed my discomfort with the wording of this criticism, and shown that translation of Hebrew and Greek into English sometimes requires changing singular nouns in the ancient languages to plurals in English, and plural nouns to singulars. Thus one must be careful when drawing implications from the “inspired singular,” especially if one implies that the singular in Greek should always be translated by the singular in English.

But, in the case of Revelation 3:20, has the TNIV in fact obscured “any possible significance of the inspired singular”? Have “individual responsibility” or “an individual relationship with Christ” been lost? In order to answer these questions, I’ll print Revelation 3:20 below in transliterated Greek, word-for-word Greek, NIV, and TNIV translations.

Transliterated Greek: Idou hesteka epi ten thuran kai krouo; ean tis akouse tes phones mou kai anoixe ten thuran, [kai] eiseleusomai pros auton kai deipneso met’ autou kai autos met’ emou.

Word-for-word Greek: Indeed/look I stand at the door and knock; if anyone should hear the voice of me and should open the door, I will come/go in to that one and I will eat with that one and that one with me.

NIV: Here I am! I stand at the door and knock. If anyone hears my voice and opens the door, I will come in and eat with him, and he with me.

TNIV: Here I am! I stand at the door and knock. If anyone hears my voice and opens the door, I will come in and eat with them, and they with me.

The Greek original uses four singular male pronouns for the person behind the door: tis (anyone), auton (him or that one, accusative), autou (him or that one, genitive), and autos (he or that one). It’s clear from the context that the male pronouns are used in this case to include either a male or a female person. This was common Greek usage, where male pronouns could indicated, not just male persons, but also persons of either sex. Thus autos pointed out a certain person (that one) without necessarily implying that this person was male (or female). |

|

| |

"The Light of the World" by William Holman Hunt (1853). This Victorian image influenced many other later paintings of Jesus. |

The NIV translates these singular Greek pronouns with singular English pronouns. Correctly following the rules of English that I learned in school, the NIV uses male singular pronouns (he/him) in a generic sense (to indicate a person whose gender is not specified). In other words, when Jesus in the NIV says, “I will come in and eat with him” this does not mean Jesus will dine only with a male, but with any individual, male or female. The English pronoun is male in form, but does not specify or imply the maleness of the individual who interacts with Jesus.

The TNIV chooses to translate the singular Greek pronouns of Revelation 3:20 with formally plural English pronouns (they/them). If you learned English the way I did, this seems to be a mistake of one kind or another. On the one hand, the TNIV may be switching from a singular person (anyone) to a group (them/they), which doesn’t make much logical sense, and doesn’t reflect the singularity of the Greek pronouns. This seems to be how the Statement of Concern reads the TNIV, since it assumes the loss of the singular. On the other hand, the TNIV may be using the formally plural English pronouns (they/them) with a singular non-gender specific meaning, which breaks the grammar rule I was taught: a singular noun without obvious gender markers (anyone) should take a singular male pronoun (he), not a plural pronoun (they). It seems obvious to me that the TNIV utilizes the second of these two options. In this translation Jesus is saying, “If anyone (singular, non-specific gender) hears my voice and opens the door, I will come in and eat with them (singular meaning, non-specific gender), and they (singular meaning, non-specific gender) with me.”

So I think the Statement of Concern has in fact misunderstood what the TNIV intends, taking the formally plural pronouns (them, they) as real plurals, when in fact they are following the singular antecedent “anyone” with a singular meaning. Thus the “obscuring any possible significance the inspired singular may have” criticism misses the target. In fact the TNIV is attempting to maintain the singular sense of Revelation 3:20 by using a formally plural pronoun with a singular meaning. After all, the TNIV did not say, “If some people hear my voice, I will come in and eat with them.” “Anyone” quite clearly shows us that the TNIV sees Jesus interacting with a singular individual in Revelation 3:20, one who is referred to as “them” and “they.”

Ironically, however, the confusion of the TNIV critics helps to buttress their point, at least somewhat. They took the TNIV as meaning, “If anyone [of a group] hears my voice and opens the door, I will come in and eat with them [that is, the whole group].” Though I think this is a mistaken reading, it isn’t impossible or silly. So the TNIV’s use of “they/them” with a singular sense does allow for some confusion, and does, therefore, potentially obscure the singular of Revelation 3:20, at least for some readers. The unambiguous singularity of the Greek singular has been lost in translation. Thus, while I think the Statement of Concern both misses the point of the TNIV and exaggerates the implications, the Statement does rightly point out a weakness in the TNIV.

This conclusion suggests several crucial follow-up questions. First, is the singular usage of “them/them” actually bad grammar, as I have suggested, the sort of grammar that should not find its way into a serious translation of the Bible? Second, why would the TNIV translators sacrifice the clarity of “he/him” by choosing to use “they/them” with a singular sense? What is the point of such a translation? What would motivate the TNIV translators to make this change from the singular clarity and grammatical orthodoxy of the NIV? I’ll begin to answer these questions tomorrow.

Is the Singular “They” Bad Grammar?

Part 13 of the series “Is the TNIV Good News?”

Posted at 11:35 p.m. on Tuesday, March 1, 2005

In my last post I showed that the TNIV uses the formally-plural pronoun “they” with singular meaning in Revelation 3:20: “If anyone hears my voice and opens the door, I will come in and eat with them, and they with me.” This is one of many such usages in the TNIV (see, for example, Romans 4:4; 8:9). But, as I noted in my previous post, this singular use of “they” breaks the grammatical rules I learned in school and have resolutely employed all of my life as an author. I have always believed that a generic pronoun such as “anyone” takes a singular pronoun, which happens in traditional English to be masculine in form (“he, him, etc.”). If a writer wants to emphasize that “anyone” could be male or female even though this is implicit in the formally singular “he,” then “he” can be changed to “he or she,” but not “they.” “He or she” may be inelegant, and, according to traditional grammarians, unnecessary, but at least it preserves the clear singularity of the antecedent.

I’ve taught New Testament Greek several times. If a student of mine had translated Revelation 3:20 in the manner of the TNIV, I’d probably have accepted that translation in what I call a “rough and ready” version (quick and unpolished, often done verbally in class). But if such a translation had been presented in a final exam, I expect that I would have, at a minimum, made some finicky comment about not using substandard English. It’s possible that I would have taken off a point as well.

But now the TNIV, a product of some of the finest Bible scholars in the world and of the highly-regarded International Bible Society, regularly uses “they” as a singular pronoun. To be honest, I find this rather surprising, even unsettling. And to be completely honest, I have always disliked the written use of the singular “they.” It grates on my grammatically pedantic ears. Am I off base here? Have the rules of English grammar changed in the last thirty years? Or are the TNIV translators doing something peculiar and improper (or, I suppose, peculiar and innovative)?

Here’s how Zondervan’s TNIV website explains what the translators have done:

The TNIV sometimes uses a generic plural pronoun in the place of a masculine singular pronoun, making it more consistent with contemporary English. . . . All of these TNIV revisions from its predecessor, the NIV, reflect a better rendition of clear gender language for the modern reader. In no cases do these updates impose upon or change the doctrinal impact of Scripture.

So Zondervan’s answer to my question appears to be, “Yes. The rules of English grammar have changed in the last thirty years. It is now correct to use ‘they’ with a singular meaning.”

I am certainly aware of the spoken use of “they” as a singular gender-non-specific pronoun. I would even grant that this is by far the dominant spoken usage in my corner of the world. In fact even I use this in casual speech. For example, if I find some French fries spilled in the back seat of my car, I’ll probably yell at my kids: “Who spilled their fries in my car?” (I have two children, a boy and a girl. To say, “Who spilled his fries in my car?” sounds prejudicial, even if grammatically proper. And “Who spilled his or her fries in my car?” sounds ridiculous.) Yet I’ve always thought that the language one uses in writing should be more formal and precise than the language one uses when yelling at his (his or her? their?) children.

| However, given the claims of the TNIV translators, I thought I should do some research into the uses of “they” as a common-gender singular pronoun. I was surprised by what I found. First, I discovered that the singular use of “they” is not some newfangled gimmick invented by the purveyors of political correctness. The Oxford English Dictionary itself includes as a definition of “they”: “Often used in reference to a singular noun made universal by every, any, no, etc., or applicable to one of either sex ( = 'he or she').” The dean of dictionaries goes on to list many classic examples of this usage. Moreover, some of the finest English writers used “they” and it’s various forms in place of a singular pronoun. These writers include: William Shakespeare (“God send every one their heart’s desire!”), Walt Whitman, William Thackery, Jane Austen, Lewis Carroll, George Bernard Shaw, J. D. Salinger, and C. S. Lewis (Voyage of the “Dawn Treader,” ch. 1). Even the King James Version of the Bible included a couple cases of where a singular antecedent takes a formally plural pronoun: |

|

| |

Jane Austen placed these words in the mouth of Jane Bennet in Pride and Prejudice: "But to expose the former faults of any person, without knowing what their present feelings were, seemed unjustifiable." |

So likewise shall my heavenly Father do also unto you, if ye from your hearts forgive not every one his brother their trespasses. (Matthew 18:35)

Let nothing be done through strife or vainglory; but in lowliness of mind let each esteem other better than themselves. (Philippians 2:3)

I surfed the ‘Net for a while to look for contemporary examples in popular writing of “they” as a singular pronoun. Not surprisingly, I found many, and I’m sure I only scratched the surface. I was a bit startled, however, to find such usage even in the London Times, “Don’t insist on carrying your suitcase; it could cost someone their job.” In addition to lots of examples of the singular use of “they,” I found three helpful websites that had sane discussions of this issue: Words@Random (Random House Dictionary page); Everybody Loves Their Jane Austen; and “A Singular Use of THEY” produced by the Attorney General’s department of an Australian commonwealth.

As a result of my little research project, I’m willing to admit that the singular use of “they” is much more common than I had realized, not only in casual, spoken English, but in written English as well. It’s certainly premature to say that “they” has overtaken “he” as the English standard version of the gender non-specific singular pronoun, but I must conclude that both are common and more or less acceptable in today’s speech. Thus the TNIV translators are not so far out of step with English grammar as I had thought. It’s no longer correct to say that “they” as a singular pronoun is a grammatical error.

Yet, given the potential ambiguity and grammatical curiosity of “they” in Revelation 3:20 and other verses throughout the TNIV, and given the ready availability of the clearly singular and grammatically orthodox “he,” we now come to the question of why the TNIV translators would regularly prefer “they” to “he” in verses like Revelation 3:20. To this question I’ll turn in my next post.

Why Does the TNIV Use "They" in Revelation 3:20?

Part 14 of the series “Is the TNIV Good News?”

Posted at 11:35 p.m. on Wednesday, March 2, 2005

I finished my last post by grudgingly acknowledging that "they" as a singular gender-non-specific pronoun shows up both in common speech and in acceptable written English. This usage is found throughout the TNIV, including Revelation 3:20: "“If anyone hears my voice and opens the door, I will come in and eat with them, and they with me.” But, given the possible misunderstanding of this use of "they" as plural, and given its peculiar sound, at least to some of us, I wonder why the TNIV translators went with "they."

I'll begin to answer this question by putting myself in their shoes. They faced the following Greek words:

Transliterated Greek: Idou hesteka epi ten thuran kai krouo; ean tis akouse tes phones mou kai anoixe ten thuran, [kai] eiseleusomai pros auton kai deipneso met’ autou kai autos met’ emou.

Word-for-word Greek: indeed/look I stand at the door and knock if anyone should hear the voice of me and should open the door, I will come/go in to that one/him and I will eat with that one/him and that one/him with me.

The context of Revelation 3:20 and the vast majority of commentators make it clear that the Greek words auton/autos, which in some places represent a male person, in this case agree with tis (anyone), which though male in form, is meant generically. To put this non-technically, Jesus is willing to come in and eat with a male or a female person. The Greek uses male grammatical forms in a generic way for an individual of either sex. (A few of the TNIV critics seem to think this verse carries some male overtones, but in my opinion they don't understand the verse or the function and nuance of New Testament Greek pronouns.)

So what options were available to the TNIV translators and what are the advantages and disadvantages of each option? I can think of several possibilities, though I'm sure there are more.

| Option |

Translation |

Strengths |

Weaknesses |

| 1 |

If anyone hears my voice and opens the door, I will come in and eat with him or her, and he or she with me. |

Clearly renders the singularity and the gender neutrality of the Greek. |

Awkward and wordy |

| 2 |

If anyone hears my voice and opens the door, I will come in and eat with that one, and that one will eat with me. |

Clearly renders the singularity and the gender neutrality of the Greek. |

Awkward and wordy |

| 3 |

If anyone hears my voice and opens the door, I will come in and eat with him, and he with me. (actual NIV) |

Clearly renders the singularity of the Greek in efficient, orthodox English prose. A good "formal equivalent" translation. |

Risk of reader misunderstanding "he" as including male but not female individuals, and so believing that Jesus will eat with males but not females. |

| 4 |

If anyone hears my voice and opens the door, I will come in and eat with them, and they with me. (actual TNIV) |

Clearly renders the gender neutrality of the Greek in efficient and possibly orthodox English prose. A Good "dynamic equivalent" translation. |

Risk of reader misunderstanding "they" as plural, and so believing that Jesus will eat, not with an individual, but only with a group. |

This chart illustrates that the most accurate renderings of the pronouns, ones that would not be misunderstood (options 1 and 2), were rejected by translators on all sides of the argument because they are awkward. I'm not criticizing the NIV or the TNIV translators for rejecting options 1 and 2. But given all the hubbub about accuracy, it is worth noting that no one prefers the most accurate translations because he or she values readability.

This chart also illustrates a point I made in Part 3 of this series, namely, that no translation is perfect. Every translation has advantages and disadvantages, so the translator must choose from among them. Rarely are things so clear that nothing is lost in translation.

It seems obvious that the TNIV translators choose option 4 because they believed that what was gained by "they" (clear gender neutrality) more than made up for what was lost (unambiguous singularity). They must have rejected "he" on the grounds that the balance of gain and loss with this translation was, in the end, not as strongly positive as with "they."

Critics of the TNIV disagree, of course. They argue that the clarity and simplicity of "he" make this the preferable translation. They tend not to acknowledge the downside of using "he" in their writings, while playing up the negatives of "they." This makes sense, given their dislike of the TNIV, but it impresses me as being too one-sided. When folks on any side of a legitimate argument can't acknowledge the weaknesses of their side, I wonder what's wrong. From my point of view, the TNIV critics could strengthen their side by admitting that their translational preferences have a significant downside as well.

If, for example, a reader were to take Jesus in Revelation 3:20 as being willing to dine with a male individual, but not a female, this would be a serious misunderstanding of the original text and a potential stumbling block to a woman reader's sense of Jesus's desire to have a personal relationship with her. The Statement of Concern by the TNIV critics rightly, in my view, points out the potential for "they" language to obscure "an individual relationship with Christ." But isn't there another side of this problem that is similarly dangerous? Couldn't the "he" language obscure the potential for a female to have "an individual relationship with Christ"? Might it even suggest to a male reader that somehow he has the inner track when it comes to knowing Jesus? These would be mistaken interpretations of Revelation 3:20, of course. But I think the "he" language runs this risk, at least with some readers.

This is when the debate over the TNIV turns from an argument about the Greek language and translation theory to an argument about English. Critics of the TNIV tend either to deny the risk I've just mentioned, or to greatly minimize it. Proponents of the TNIV tend to magnify the risk. In particular, folk on the pro-TNIV side have argued that the English language has been changing quite rapidly, and that the formerly standard generic "he" has been eclipsed by the now common generic "they." This is especially true, so say the TNIV folk, among younger readers, the people to whom the TNIV is targeted.

In my next post I will take on this disagreement about contemporary English, which will lead into the larger debate about the use or non-use of inclusive language in today's English. This debate about English, it seems to me, turns out to be one of the most important issues of all, perhaps the most important. If it is true that there really are a substantial number of people who don't understand "he" and other such terms generically because of how they speak English, then the case of the TNIV critics is badly weakened. But if, on the other hand, the vast majority of English speakers understand male generic English terms, then the rationale for the TNIV is undermined. So, I'll sail into this tempest tomorrow. |

|

| |

Hold on to your hats! We're going in.

|

How Common Is Inclusive Language in Today's English?

Part 15 of the series “Is the TNIV Good News?”

Posted at 10:35 p.m. on Thursday, March 3, 2005

In many ways the debate about the TNIV Bible translation seems to boil down to one basic question: "How common is inclusive language in today's English?" Yes, of course there are other key issues in the debate, including: the nature of translation, the "nuances" of Greek and Hebrew language, the impact of modern feminism, and so forth. But, it seems to me, one clear point of difference between pro-TNIV and anti-TNIV forces is their estimation of how widespread is the use of inclusive gender language in contemporary English.

Because translation has to do, not only with the words and meanings of the source languages (Hebrew, Aramaic, Greek), but also with the words and meanings of the target language (English), then an accurate appraisal of how English is spoken today is a crucial factor in the evaluation of any translation, including the TNIV. If it turns out, as the pro-TNIV folk allege, that contemporary English usage has changed quite a bit since the NIV was published, and that a key aspect of that change involves the common use of inclusive language for people, then the case for the TNIV is strong. If a large number of English speakers use gender inclusive language and might not readily understand traditional male generic language, then we might very well need a Bible that uses this sort of language. After all, shouldn't Bible translators seek to translate God's timeless Word into the language of a given time and place, even if there are aspects of that language that we don't appreciate? Conversely, if it turns out, as the anti-TNIV claim, that traditional male generic language is still very common in English and would be readily understood by almost all readers, then one of the apparent strengths of the TNIV loses its significance, and may in fact be a weakness.

Given the central importance of the question of how common inclusive language is in today's English, it comes as no surprise that the controversy over the TNIV often focuses here. Yet, I must confess that I have been surprised by the volume of e-mail I've received on this topic, even before I've weighed in on it. I've already had many readers lobbying me on both sides. Some believe that the claims of the TNIV translators are a lot of nonsense, that English hasn't changed all that much, and that those want inclusive language Bibles should just stop whining. Others among my readers have wanted me to know that they and their contemporaries never use "he" generically, and would find a Bible that did so to sound very odd.

So what are we to make of the official disagreement by TNIV proponents and opponents, not to mention the ad hoc and unofficial disparity among readers of my blog? Is there any common ground that is solid enough on which to build something other than a house of cards?

Yes, I believe there is. First of all, the very fact of the disagreement about English usage seems to prove the following:

Inclusive Language in Contemporary English, Thesis 1: In contemporary English usage there is a wide range of practice when it comes to inclusive language.

I don't see how any objective person could dispute this. This very day thousands of English speakers and writers used "he" generically. And this very day thousands of other English speakers used "they" as a generic singular. One writer will use "man" generically; another will use "humanity" instead. And so forth and so on for the other cases of gender language.

I've seen both sides of the debate attempt to argue that their language usage is more common, or more progressive, or more grammatically orthodox, or more godly, or whatever. But no matter who in the end is right about such things, I still believe that we must acknowledge the fact that in contemporary English usage there is a wide range of practice when it comes to inclusive language.

Now, is there anything else about inclusive language in contemporary English that most objective people might agree about? Yes, I think so, though what follows is less certain than Thesis 1, in my opinion. In fact, it's all my opinion, based upon my experience and superficial research. I'm neither a linguistic nor a sociologist, so as you read what follows, consider the source!

Inclusive Language in Contemporary English, Thesis 2: The use of inclusive gender language is more common among younger speakers, though this fact can be exaggerated.

According to the Zondervan, publishers of the TNIV:

Perhaps the most important reason to produce a new translation is to reach today's generation of 18- to 34-year-olds, a generation that is leaving the church in record numbers. . . . While older forms of English may not present a problem for some readers, they can present barriers to understanding and fully engaging the Bible for today's generation because they've grown up using more contemporary English. . . . 77% of 18-34 year-olds prefer the text of the TNIV.

Moreover, Zondervan claims,

Both the NIV and TNIV are extremely accurate translations for their intended audiences. However, the TNIV is more precise in its language, creating a highly readable Bible for today’s generations that reflects the most recent advances in biblical scholarship.

Even school and college textbooks have changed over the years, as “men” rarely refers to both men and women today.

I have yet to find a direct quote in which Zondervan claims that younger speakers in fact use inclusive language more than older speakers, but this is surely implied in their promotional material. Moreover, some who have supported the TNIV have made this claim more directly.

I would love to see hard evidence for or against this thesis. Perhaps someone has done a survey of actual language usage among 18-34 year olds. Unfortunately, I haven't found much along these lines, though I did surf my way into a couple bits of evidence.

The GodAndScience.org website contains an article by Wesley Ringer called "What are the Biblical Translation Issues Raised by the Gender-Inclusive Debate?" This is a very balanced, fair appraisal of the issues by someone who seems to be open to but not excited about the value of the TNIV. Mr. Ringer, in writing his piece, did some informal research among young adults, the majority of whom were students at Biola University (an evangelical Christian institution), though some were from Pasadena City College. What he found was that the majority of students approved of traditional male gender language, though a substantial minority did not. Disapproval was even more pronounced among the non-Christian students. Mr. Ringer's survey was not intended to be scientific. But it indicates that there is diversity of inclusive language practice among younger people. Students from a conservative Christian college, in particular, did not prefer inclusive language. (Note: there is no date in Ringer's article, though he cites a book from 2002 and refers to 2003 in the future, so it must have been written in 2002.) |

|

|

Above: students from Biola University. Almost anyone in this picture would choose the NIV for his Bible.

Below: Catholic students from Macquaire University in Australia, enjoying, what else, a bit of barbie. Odds are somone in this picture would prefer the TNIV for their Bible.

|

|

The second bit of evidence I've found for inclusive language usage among younger speakers comes from an article I had mentioned previously: "A singular use of THEY," produced by an attorney general's office in Australia. This article also seems to be balanced in its approach. One substantial section is called "How popular is THEY?" This section referred to a couple of studies done in Australia. Here's how the article describes the results of a 1994 study done by the Dictionary Research Centre of at Macquarie University

[T]he use of they [as a generic, as opposed to he alone] with everyone and anyone was strongly preferred overall, and with the under 25 age group reached 98%. However, older participants, especially those in the 65+ group, were less supportive, perhaps still feeling the chastisements of school lessons. The results are unmistakable, however: there is a widespread acceptance of they.

Since I cannot find the actual study online, I cannot evaluate the evidence behind these claims. But they do seem to support rather strongly the contention that younger speakers would use a generic singular "they" while older speakers would do with the traditional "he."

Summing up the evidence, modest as it is, Wesley Ringer's survey suggests that evangelical American students lean toward "he" as a generic while the Macquarie University study shows that Australian young people strongly prefer "they." Two studies of this sort could hardly be considered conclusive. But they do suggest that there is a fair amount of diversity among younger folk when it comes to the use of inclusive language. This would also be true in my own experience as I interact with people of ages 18-34. Some use inclusive language consistently, others don't. If such diversity is truly the case, then Zondervan's implication about the need for the TNIV in order to reach younger people in general is an exaggeration, even though it is true that millions of people in this age bracket would prefer a gender-inclusive translation. Perhaps Zondervan ought to market the TNIV at Macquarie, but bypass Biola.

So far I've put forth two theses with respect to inclusive language in today's English. I have a couple more theses, which I will offer in my next post in this series. Stay tuned . . . .

Inclusive Language in Today's English: Another Thesis

Part 16 of the series “Is the TNIV Good News?”

Posted at 11:55 p.m. on Sunday, March 6, 2005

A brief review: My examination of the TNIV controversy led me to look at the use of inclusive language in contemporary English. This turns out to be a crucial point in the discussion, and one about which there is considerable disagreement. Those who endorse the TNIV tend to emphasize the pervasiveness of gender inclusive language, especially among younger people. And, not surprisingly, those who dislike the TNIV tend to believe that inclusive language is much less common than the other side claims.

In my last post in this series I proposed two theses relative to the use of inclusive language in today's English. They were:

Inclusive Language in Contemporary English, Thesis 1: In contemporary English usage there is a wide range of practice when it comes to inclusive language.

Inclusive Language in Contemporary English, Thesis 2: The use of inclusive gender language is more common among younger speakers, though this fact can be exaggerated.

If you're interested in why I believe these theses to be true, you should check my last post. Today I'll add one more thesis:

Inclusive Language in Contemporary English, Thesis 3: People who actively participate in conservative evangelical Christian communities are less likely to use inclusive gender language and more likely to be comfortable with traditional male generic language.

This thesis isn't especially profound. In fact it's rather obvious. But it does help to explain, I think, why folks on opposite sides of the TNIV debate seem to be talking right past each other much of the time. Listen to the folks who translate the TNIV, and you'd think most English speakers use inclusive language. Listen to their opponents and it sounds like they live on another linguistic planet. I believe that, in some sense, they do.

Specifically if people spend most of their time in Christian communities that use a traditional language Bible (KJV, NKJV, NIV, ESV, NASB, etc.), and if they themselves have used one of these translations for years, both in study and in personal devotions, then they will be very familiar and comfortable with male generic language. Gender inclusive language will sound strange, forced, and unnecessary. In fact, it will sound "politically correct" rather than grammatically correct.

Yet if people spend most of their time in Christian communities, even solid evangelical communities, where inclusive language is more common, and if they themselves use Bibles that employ inclusive language (NLT, NRSV, CEV, GNB, NCV), then they will be more familiar and comfortable with gender inclusive language. Male generic language will sound strange, archaic, and oddly exclusive. This will be even truer for Christians who spend a good chunk of their time communicating with people outside of the Christian community, especially if these folks are a part of secular academia. And it will be truer still of people who are not Christians and who spend most of their time in secular environments.

Now I haven't done the sort of scientific study that would prove this thesis, but I have seen evidence to support it. In my last post I cited two studies, one by Wesley Ringer, in which he surveyed students from Biola University and Pasadena City College. The other was done by the Dictionary Research Centre of Macquarie University in Australia. This Australian survey found that people under age 25 had a strong preference for inclusive language. Wesley Ringer, on the contrary, found that students at the conservative Christian Biola University were much more comfortable with traditional language. Yet, though he didn't survey too many students from Pasadena City College, Ringer found that they tended to fall more in the inclusive language camp.

I don't think one has to be a rocket scientist, a linguist, or a sociologist to make sense of this data. Our feeling for a language, for what is common and uncommon, for what is correct and incorrect, reflects our own experience, how we speak, what we hear, and what we read. Largely, it reflects the linguistic communities in which we make our homes. Even in this day when mass media has flattened out so many regional differences in language, some genuine differences still exist. Recognition of this fact among Christians would help, I think, to make the debate about the TNIV both more civil and more productive.

Let me provide an example of how one English language differences can be surprising. I grew up in Southern California. When I was, eighteen I moved to the Boston area for college. I spent the next eight years there before returning to California. While I was in Boston, I learned that the locals used many words in a way quite unfamiliar to me. At home in Los Angeles, I'd go to a convenience store to get a soda. In Boston, I'd go to a spa to get a tonic. At home I knew the difference between regular coffee (caffeinated) and Sanka (decaffeinated). In Boston I was another linguistic world.

I remember one of my first visits to the Mug n Muffin Restaurant in Harvard Square. I ordered a blueberry muffin and a cup of coffee.

"Regular?" the waitress asked gruffly.

"Sure, regular," I replied.

I knew I needed a bit of caffeine flowing through my veins while I studied. A few minutes later the waitress returned with my muffin and coffee. I immediately noticed that the coffee wasn't black like I had expected, but light brown. Taking a sip, I tasted lots of sugar, which I never put in my coffee. |

|

| |

The Mug n Muffin, one of my favorite hangouts, is no longer, I'm sorry to say. |

"Excuse me," I called to the waitress, "my coffee isn't right. It has cream and sugar in it."

"You wanted it regular," she replied, impatiently."

"Yes, regular, not Sanka," I said. "But I didn't ask for cream and sugar."

"You said regular," she shot back, "regular, that's cream and sugar. That's what you got!"

"Oh!" I replied, realizing that I had lost the argument, and could only dig myself in deeper by my protestations. So I submissively drank that cup of coffee, and never again ordered coffee regular. Black was how I wanted my coffee, black, not regular. If I was going to be a happy coffee drinker in Boston, I needed to change the way I spoke.

The TNIV controversy makes more sense to me if I realize that those who support this translation like their coffee black, while those who oppose it like their coffee regular. Of course for them the issue isn't coffee, but gender. Many of their disagreements stem, I think, from the fact that their language worlds differ significantly when it comes to inclusive language. This fact helps me to understand why so many godly, mature, biblically-committed evangelical leaders endorse the TNIV, while so many godly, mature, biblically-committed evangelical leaders have withheld their support for this translation. Those who live in communities where inclusive language is the norm desperately feel the need for a translation that communicates in their world. And those who live in communities where traditional language is the norm don't feel this need at all, and can't really understand the motivations of their evangelical brothers and sisters. That's one reason why they end up accusing them of succumbing to the demands of political correctness. Because traditional language seems so normal to them, they can't quite relate to why others would work so hard to translate God's Word into inclusive idioms.

There is another crucial difference in the way today's inclusive language functions, but this will have to wait until tomorrow.

Inclusive Language in Today's English: Thesis 4

Part 17 of the series “Is the TNIV Good News?”

Posted at 9:45 p.m. on Monday, March 7, 2005

To review, here are my first three theses:

Inclusive Language in Contemporary English, Thesis 1: In contemporary English usage there is a wide range of practice when it comes to inclusive language.

Inclusive Language in Contemporary English, Thesis 2: The use of inclusive gender language is more common among younger speakers, though this fact can be exaggerated.

Inclusive Language in Contemporary English, Thesis 3: People who actively participate in conservative evangelical Christian communities are less likely to use inclusive gender language and more likely to be comfortable with traditional male generic language.

Theses 2 and 3 are actually sub-theses of #1. They spell out ways in which the actual practice of inclusive language is diverse: by age groups (and even within age groups), by Christian experience/community.

Today I want to add one more thesis that identifies another kind of variation:

Inclusive Language in Contemporary English, Thesis 4: There are different kinds or degrees of inclusive language.

What I mean by different kinds or degrees of inclusive language is that many speakers will use inclusive language with some words or in some context by not in others. Similarly, many people will tend to hear some masculine English words as inclusive of males and females, while hearing others as referring exclusively to males. So generalizations about "inclusive language" are sometimes far too general to be really helpful in the TNIV debate.

If you've been reading along for a while, you know that I got into this whole issue by way of Revelation 3:20 ("I stand at the door and knock. If anyone hears my voice and opens the door, I will come in and eat with him/them, and he/they with me.") Thus I've been referring to the inclusive use of "they" as a singular generic pronoun and the non-inclusive use of "he" as a singular generic pronoun. But of course there are many more words involved in the inclusive language debate over the TNIV. The "Statement of Concern" released by the TNIV's opponents includes these examples where the TNIV changes words translations found in the NIV:

• "father" (singular) to "parents";

• "son" (singular) to "child" or "children";

• "brother" (singular) to "someone" or "brother or sister," and "brothers" (plural) to "believers";

• "man" (singular, when referring to the human race) to "mere mortals" or "those" or "people";

• "men" (plural, when referring to male persons) to "people" or "believers" or "friends" or "humans";

• "he/him/his" to "they/them/their" or "you/your" or "we/us/our"; and

Many people might, in their own speech, use some of these inclusive terms and, in other contexts, some of the masculine terms. For example, someone might regularly use "man" as the generic term for all people, for humanity, if you will, and yet never use the term "men" in reference to a group of male and female adults. Similarly, someone might hear the term "man" as a common and inoffensive way of speaking about all people, and yet hear "men" as including adult males only.

I think of my own congregation, for example. I haven't surveyed their usage of or preference for inclusive language. My guess is that I'd find quite a bit of diversity within my church family, including diversity with respect to kinds or degrees of inclusive language. Let me provide some specific examples. Most are hypothetical, but the first really happened.

Example #1: In last week's sermon I was talking about different ways of translating the Hebrew adjective na’wa. In some places it means "fitting" and in other places it means "lovely," depending on context. Here's an excerpt from my sermon:

The adjective translated here as "fitting" appears several other times in the Old Testament. It shows up in the Song of Solomon, for example, when the man says to his beloved, "Your face is lovely" (2:14), or when the beloved says, "I am black and beautiful" (1:5). (Note to the men: If you want to make your wife happy, don't tell her that her face is fitting. Wouldn't be prudent. Try lovely or beautiful instead.)

When I began this humorous aside by saying, "Note to the men," I'd guess that 100% of those who heard this phrase understood me to be addressing the male adults, even before I made this clear by referring to "your wife." Not a single person who heard me last weekend would have thought that my "note" was for male and female adults. For my congregation, "men" means "male adults" unless it is used in some context where we expect unusual language patterns (like an older hymn, for example).

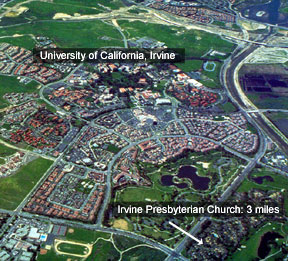

| Example #2: But suppose in this same sermon I was making a serious theological point by saying, "There is a great gulf between God and man, which only Christ can bridge." In this case I think 100% of those who heard this phrase would understand "man" in the broadest sense as "all humanity." Not a single person would have thought I was talking about a chasm between God and male human beings alone. Moreover, I doubt that very many people if any would be put off by my use of "man" in a generic sense, though some, especially those associated with the local campus of the University of California (Irvine) might find my use of "man" a bit dated. If I had visitors from the UCI who were not Christians and not familiar with Christian language – as is often the case – they might take offense at my use of non-inclusive language. It's possible that my point about God and man/humankind would have been obscured by my choice of traditional rather than inclusive language. |

|

| |

An aerial view of the University of California, Irvine. My church is about three miles to the north. We have a growing number of UCI students, staff, and faculty at our church.

|

Example #3: This example is rather like the first, only using the word "brothers." If I were to say in a sermon, "God calls me to love my brothers in Christ," the vast majority of my congregation would think I was talking specifically about my need to love other Christian males. A few might understand "brothers" more generically, but not many.

Example #4: Similarly, suppose I were to say, "If a brother sins against me, Jesus tells me to go to him and show him his fault when we are alone," almost every person in my congregation would hear this as a specific reference to a male Christian, not to any Christian, male or female.

Example #5: If, however, I picked up a Bible and read, "If your brother sins against you, go and show him his fault, just between the two of you," most people would understand that I was using a translation that used more traditional language. This quotation is the NIV of Matthew 18:15a. There would be some people, however, especially those unfamiliar with the Bible, including younger folks in elementary school, who would think that Jesus was in fact was talking about a male brother only, not a generic brother or sister.

These examples, though mostly hypothetical, illustrate my thesis about different kinds or degrees of inclusive language usage. In these cases I have focused on what people would understand when hearing masculine language that could be generic or could be referring to males (as opposed to females). The same people would hear some terms, like "men," as referring solely to males, while other terms, like "man," as being more inclusive. A similar pattern would be found in the way people speak.

If my four theses about the use of inclusive language in today's English are anywhere near correct, then much of the debate about the TNIV is far too simplistic. People on both sides of the argument seem to minimize the diversity of genuine usage in order to bolster their arguments for or against the TNIV. It's easier to sell this translation by claiming that "today's English" is gender inclusive. And it's easier to get folks upset about the TNIV by minimizing the actual usage of inclusive language today or lumping it all together into some sort of feminist plot. The reality of today's English, at least in my observation and surely in my particular world, is much more complex and nuanced than some appear to think.

Since I've brought up the language of "siblinghood" in this post, I'll stay with this theme in my next post by examining the anti-TNIV criticism in the "Statement of Concern" regarding the TNIV's changes in "brother" language. (Siblinghood! How's that for an inclusive language tongue twister? Just for fun I "Googled" it and got 786 hits.)

Concerns Over Luke 17:3 in the TNIV

Part 18 of the series “Is the TNIV Good News?”

Posted at 11:55 p.m. on Tuesday, March 8, 2005

My exploration of the issues involved in the TNIV controversy led me to the core issue of inclusive language. As I have shown in recent posts, this issue is not nearly as simple as it is sometimes portrayed by those arguing for or against the TNIV. The actual use of gender inclusive language in today's English is complex is many ways, and this make the issue of translation similarly complex.

Nevertheless, I want to return to the "Statement of Concern" signed by over 100 evangelical leaders who oppose the TNIV. Central to this statement is a critique of the TNIV's use of gender inclusive language. The Statement refers specifically to unacceptable ways that the TNIV renders male generic language by adding words. Here's an excerpt from the Statement:

The TNIV translation inserts English words into the text whose meaning does not appear in the original languages. For example, in Luke 17:3, the translators changed "If your brother sins, rebuke him" to "If any brother or sister sins against you, rebuke the offender." The problem is, the word "sister" is not found in the original language, nor is "against you," nor is 'offender.'

Before I examine Luke 17:3 and the TNIV's translation, I've got to express some frustration with the wording of this paragraph in the "Statement of Concern." If you've been reading this series for some time, my unhappiness will sound familiar.

For one thing, it's misleading to say, "The TNIV translation inserts English words into the text . . . ." When we're talking about translations, "text" refers to the original language document, in this case the Greek of Luke 17:3. The way the Statement of Concern reads, one might be led to think that the TNIV translators actually added English words to the original text, which is obviously untrue. In fact they translated the Greek words of the text into the English words they believed best represented the meaning of the text itself. They may have made mistakes, of course. But when the TNIV critics talk about "inserting words into the text" their imprecision isn't helpful for those of us who are looking for a clear, fair discussion of the real issues.

Second, if you check this paragraph from the "Statement of Concern" with the TNIV itself, you find a perplexing inaccuracy. Let me compare what the Statement claims is the TNIV's translation of Luke 17:3 with what the TNIV really says:

| Statement's "TNIV" version of Luke 17:3 |

If any brother or sister sins against you, rebuke the offender. |

| Actual TNIV version of Luke 17:3 |

If a brother or sister sins against you, rebuke them. |

I don't know what to make of this. Perhaps the "Statement of Concern" was written in response to some earlier version of the TNIV. I have no idea if this is true. But even if this is the case, I find the inaccuracy of the Statement to be quite unimpressive. I know it might seem like I'm quibbling here. But, given the fact that this debate is about accuracy and the meaning of words, I would expect the authors and signers of the "Statement of Concern" to work harder to insure the accuracy of their own words. Don't you think that at least one of the 100 signers would have flagged this mistake and made sure that is was corrected? [Note added on March 9: A reader of my blog has confirmed my hypothesis about an earlier version of the TNIV. This explains why the "Statement of Concern" reads as it does. I hope the "owners" of this Statement correct it to reflect the TNIV as it is today.]

The final sentence of this paragraph from the "Statement of Concern" reads, "The problem is, the word 'sister' is not found in the original language, nor is 'against you,' nor is 'offender.'" Once again I find this way of talking about translation for too imprecise. "Sister," "against you", and "offender" would never appear in the original language since these are English words, not Greek words. At issue is not whether these English words are found in the Greek text, but whether it is appropriate to translate the actual Greek words of Luke 17:3 with these English words, among others.

By definition, translation involves changing words from one language to another. Accurate translation often demands adding to or subtracting from the number of words in the original language. For example, Luke 17:3 includes the Greek words ean hamarte ho adelphos sou epitimeson auto (if should sin the brother of you rebuke him/that one). The NIV translates ho adelphos sou as "your brother," not as "the brother of you." Three Greek words have become two English words in the NIV. But this is not a mistake. It would be misleading if one were to criticize the NIV for "taking away a word from the inspired text" or "changing the words of the original."

Looking beyond the imprecision of the actual words of the "Statement of Concern" and focusing instead on the meaning of the Statement, I find three main criticisms of the TNIV:

1. In Luke 17:3, the TNIV translates adelphos, which literally means "brother," with "brother or sister," where the NIV uses only "brother."

2. In Luke 17:3, the TNIV translates hamarte, which literally means "sins," as "sins against you," where the NIV uses only "sins."

3. In Luke 17:3, the TNIV translates epitimeson auto, which literally means "rebuke him/that one," with "rebuke the offender," where the NIV uses only "rebuke him."

Let me tackle these criticisms in reverse order. Criticism #3 misrepresents the TNIV, as I mentioned above. In fact the translation reads "rebuke them." I've already had plenty to say about the use of "them" as a singular generic. Though I don't like this usage, I recognize that it is common both in speech and writing. Obviously the TNIV translators used "them" in order to avoid "him" and the potential limitation of the sentence to a male only. The TNIV critic would say that "him" has a generic meaning, so "them" is both unnecessary and unclear.

I would tend to agree with Criticism #2. It is most likely that the original Greek text of Luke 17:3 contained only ean hamarte ho adelphos sou (literally, if your brother should sin) and not ean hamarte eis se ho adelphos sou (literally, if your brother should sin against you). Though I wouldn't say that the TNIV adds the phrase "against you" to the text, I would say that it translates a Greek verb that means "sins" with a more specific "sins against you." This adds meaning that was not obvious in the original Greek.

I am not comfortable, however, with the criticism offered by one of the TNIV's critics. About the inclusion of "against you" in Luke 17:3 he writes, "The words 'against you' are inserted into the Bible but they have no basis in the Greek text." Apart from the imprecise "inserted into the Bible," the claim of "no basis in the Greek text" is too strong on two accounts. First, there actually is some basis in the Greek text for including "against you," since a large number of Greek manuscripts of Luke do in fact include this phrase. Most text critical experts believe that this eis se (against you) was not original, but one could debate the evidence. Notice, in particular, that the KJV of Luke 17:3 reads "If thy brother trespass against thee . . . ." (emphasis added). I don't think the "against you" should be included, but I think "no basis in the Greek text" overstates the case.

Second, if you look at the larger passage in which Luke 17:3 is a part, you find at least some textual support for "against you." Here is this passage in the NIV: |

|

| |

This ancient Greek manuscript (Bezae, 6th century) shows a portion of Luke 6. It includes the words eis se ("against you") in Luke 17:3. |

If your brother sins, rebuke him, and if he repents, forgive him. If he sins against you seven times in a day, and seven times comes back to you and says, "I repent," forgive him. (Luke 17:3b-4, NIV)

In verse three the brother merely sins. In verse four, however, he "sins against you." On the basis of verse 4, taking into consideration the parallel verse in Matthew 18:15 ("If your brother sins against you"), one could argue that Jesus's meaning in 17:3 is, in fact, "if your brother sins against you." There is a strong basis for this interpretation in the text, not in its literal words, but in its meaning.

Nevertheless, I believe the TNIV provides more data than the Greek actually supplies, and adds an interpretation – albeit a correct one – that is more a matter of exposition than of translation. In my opinion, Luke 17:3 in the TNIV should have read, simply, "If your brother or sister sins, rebuke them."

But what about the crux of the criticism, which is the use of "brother or sister" instead of the NIV's "brother"? I'll take this up in my next post.

Oh Brother! Inclusive Language in Luke 17:3

Part 19 of the series “Is the TNIV Good News?”

Posted at 11:15 p.m. on Wednesday, March 9, 2005

Yesterday I began to examine the criticism leveled by critics of the TNIV at the TNIV translation of Luke 17:3. Today I get to the heart of the criticism.

Luke 17:3 reads in the TNIV: "If a brother or sister sins against you, rebuke them." Yet the original Greek text contains only the Greek word for "brother" (adelphos), not the word for "sister" (adelphe). Thus critics of the TNIV accuse the translation of adding words that are not in the original. Yesterday I explain that the mere fact of "adding words" doesn't count for or against a translation, since translating from one language to another often includes using more or less words than the original text. So the real issue before us is not whether the TNIV translators added the word "sister," but whether this is a reasonable translation of the Greek text.

Earlier in this series I explained the difference between two dominant philosophies of translation, formal equivalence and dynamic equivalence. Formal equivalence, in a nutshell, seeks to preserve the "forms" of the original language, and is often called "word-for-word" translation. Dynamic equivalence is more concerned to capture the meaning of the original in the target language, even if this requires a loss of formal equivalence. Dynamic equivalence is sometimes called "thought-for-thought" translation. If one approaches Luke 17:3 from the perspective of formal equivalence, then the use of "or sister" is unwarranted. The Greek words h adelphe do not appear in the original text.

The critics of the TNIV seem to adhere to a formal equivalence philosophy, so they are understandably displeased with what the TNIV does with Luke 17:3. But their disagreement really isn't about that verse or the use of "or sister" so much as the whole philosophy of dynamic equivalence. The vast majority of their specific examples of "problems" with the TNIV could be summed up in a simple statement: The TNIV uses a "thought-for-thought" translation philosophy, which we believe is wrong. Period.

For the record, the TNIV translators are not trying to fool anybody by using a dynamic approach. There is no stealth involved here, as is obvious from the introduction to the TNIV:

The first concern of the translators has continued to be the accuracy of the translation and its faithfulness to the intended meaning of the biblical writers. This has moved the translators to go beyond a formal word-for-word rendering of the original texts. Because thought patterns and syntax differ from language to language, accurate communication of the meaning of the biblical authors demands constant regard for varied contextual uses of words and idioms and for frequent modifications in sentence structures.

To achieve clarity the translators have sometimes supplied words not in the original texts but required by the context. . . . |

|

| |

A colorful version of the TNIV. |

Luke 17:3 is a good example of this approach. Therefore, if you think dynamic equivalence is mistaken in general, you'll disapprove of Luke 17:3 and a host of other verses.

But just because one believes that there is some merit in dynamic equivalence, this does not necessarily imply that the TNIV translation of Luke 17:3 is acceptable. I have already expressed my unhappiness with the use of the words "against you" in "If your brother or sister sins against you." Though I agree that Jesus implies this, I would prefer to let the ambiguity of the original language stand.

But what about "or sister"? Does the translation "If your brother or sister sins" render Jesus's meaning accurately, even though the Greek lacks e adelphe?

We can be fairly sure that Jesus used the Aramaic word 'ach when he talked about a brother sinning. This was translated with the Greek word adelphos by the early Christians, and Luke, writing in Greek, adopted this usage. When Jesus first spoke of a brother sinning, his hearers would probably have thought he referred to a fellow Jew, though by Luke's day the text was understood as referring to a fellow Christian. The Aramaic word 'ach, which literally meant male sibling, was used in the language of Jesus's day to describe a kinsman or a fellow Israelite. This term, though grammatically masculine, could be understood generically or in a representative sense, which would include a woman as well as a man. Thus every commentator I checked confirms the obvious sense of Luke 17:3. Though Jesus speaks of a "brother" sinning, his teaching was meant to apply both to males and females. He didn't need to use the word "sister" to be inclusive because 'ach, rendered as adelphos in Luke 17:3, clearly included women as well as men.

The challenge for the translator who operates with a dynamic equivalence philosophy, therefore, is to render 'ach into the most intelligible English. For centuries this posed no problem, because like the Aramaic 'ach and the Greek adelphos, "brother" was heard inclusively. Though a masculine form, it had an inclusive meaning. Thus it would have been both wordy and bad English if the King James Version, for example, had translated Luke 17:3: "If thy brother or sister trespass against thee." Everybody knew that "brother" represented the sisters as well.

The translators of the TNIV (and also the CEV, NLT, and NRSV) believed that "brother" alone did not adequately convey the sense of the original Greek. In their view, "brother" would not be heard inclusively enough, and might suggest that Jesus was speaking only of a man sinning. So the TNIV translators, seeking to clarify the true meaning of Luke 17:3, opted for "brother or sisters" in place of the NIV's "brother." (The CEV chose "followers of mine;" the NLT used "believer," and the NRSV went with "disciple." No matter whether we like the TNIV's translation or not, at least we can admire its effort to remain close to the original sense of adelphos. It is less free a translation, if you will, than other recent dynamic equivalence translations.)

Now the issue before us is a question more about English meaning than Greek or Aramaic meaning. Does "brother and sister" accurately render Jesus's original meaning in today's English? Would "brother" by itself be inadequate? Yes, say the translators of the TNIV. No, say their critics. I'll try to answer this question next time, say I.

Oh Brother! Inclusive Language in Luke 17:3 (cont)

Part 20 of the series “Is the TNIV Good News?”

Posted at 11:15 p.m. on Thursday, March 10, 2005

Yesterday I examined the use of inclusive language in the TNIV translation of Luke 17:3. Although the Greek text reads (in a very literal translation), "If your brother should sin, rebuke him," the TNIV renders this verse as "If a brother or sister sins against you, rebuke them." The translators of the TNIV, rightly believing that the use of "brother" in this passage was surely meant to include both male and female "siblings" (fellow Jews and/or fellow Christians), rendered the sense of adelphos (Greek, "brother") not with the formally equivalent "brother" but with the dynamically equivalent "brother or sister."

Or at least they would claim that "brother or sister" accurately conveys the actual meaning of adelphos. But TNIV critics have argued that this translation is inaccurate and unnecessary. After all, English has the word "brother," and it has more or less the same meaning as the Greek word adelphos. It can refer to a literal relative or to someone who is relationally close though not actually related. For centuries, "brother" was used in a generic or representative sense, where the singular "brother" had the connotation of "brother or sister," though this was not stated because it didn't need to be. Thus when the KJV said "If thy brother trespass against thee" or the RSV said "If your brother sins" both the translators and the readers understood that this passage applied equally to a sister. This continues to be true today, say the critics of the TNIV. Thus Luke 17:3 in the ESV, the translation produced by the leading TNIV critics, reads simply, elegantly, and traditionally, "If your brother sins, rebuke him."

Among those who differ over the TNIV, there is no disagreement about what the original Greek text says. Nobody is trying to smuggle adelphe (Greek for sister) into the biblical manuscripts. And, to my knowledge, there is very little disagreement about the scope of Jesus's concern. It applies to women and well as to men. So the point of difference has to do with the adequacy of "brother" in this instance. And this is a matter mostly of English meaning and language usage today. The TNIV translators would say that "brother" no longer carries the inclusive sense it once carried in English, and must be supplemented by "or sister" for the sake of accuracy. The TNIV critics would counter that "brother" can still be understood in a more inclusive sense, and that there's no sufficient reason to add "or sister" to the translation of Luke 17:3.

So who's right? The translators? The critics? Neither? Both? Although it might seem that I'm making a logical mistake, I'd tend to answer all of these questions with "Yes!" The translators are right that today's English no longer understands "brother" in an inclusive sense in some communities of English speakers. The critics are right that today's English still uses "brother" inclusively in some communities of English speakers. Neither side is right if it tries to argue that all (or even the clear majority of) English speakers are on their side. And both sides are right once you acknowledge the wide diversity of inclusive language usage in today's English.

When I read the volleys back and forth between TNIV supporters and TNIV critics, it almost seems at times like they live in different worlds and speak different versions of English. In a sense, I think this is true. Last week I put up several theses about inclusive language, two of which read:

Inclusive Language in Contemporary English, Thesis 1: In contemporary English usage there is a wide range of practice when it comes to inclusive language.

Inclusive Language in Contemporary English, Thesis 3: People who actively participate in conservative evangelical Christian communities are less likely to use inclusive gender language and more likely to be comfortable with traditional male generic language.

Although most of the TNIV translators actively participate in "conservative evangelical Christian communities," they seem to be more in touch with a wider diversity of English usage, one in which "brother" no longer has a representative or inclusive meaning. The TNIV critics, who really do want today's English speakers to understand the Bible, nevertheless appear to believe that "brother" is widely and easily understood inclusively by the vast majority of today's English speakers. This, in my opinion, is largely a reflection of their own language usage and that of their primary communities. (Yes, they can find examples in secular media of usage that fits their own patterns, but such lists seem to me almost self-defeating. If their point about contemporary English was so obvious, they wouldn't need the lists.)

The tendency of TNIV critics to assume that their experience is common to most speakers accounts for what otherwise seems to me a serious shortcoming in almost all of the criticisms of the TNIV. The critics point out, rightly I think, the potential misunderstandings when the TNIV uses "they" in place of the NIV's "he," or "brother and sister" in place of the NIV's "brother." But they seem almost completely unaware of the potential misunderstanding on their side of the aisle. Or they are aware of this potential misunderstanding, but consider it either so unlikely or so unimportant that it's not worth mentioning. But their failure to acknowledge the weaknesses of their own side does not, in my view, strengthen their argument because these weaknesses are quite real and deserve to be taken seriously. In the end it may still be best to go with a more formal equivalence translation when it comes to gender language, but every Christian leader who makes this choice should be well aware of the potential misunderstandings it can bring so these can be addressed in teaching, preaching, etc.